The best acoustic guitars in the world have historically been made from specific types of wood, such as spruce, cedar and rosewood. Is it just tradition or is it backed by science?

Part of the answer lies in the properties of the wood itself. An exhaustive piece of research conducted in the late-1970s evaluated 25 wood species (across 87 wood samples) which had been used to make high-quality musical instruments including guitars, violins and pianos.

“Spruce is nearly the unanimous choice for violin tops, guitar tops, and piano soundboards,” according to Daniel W Haines’ paper, On Musical Instrument Wood.

“Maple enjoys a similar position for violin backs as does rosewood for guitar backs. Tradition extends to how the wood is cut from the tree and to preferences for certain species. Why is this so? We believe the answers rest in certain musically related mechanical properties of these woods, namely stiffnesses, density and vibrational damping.”

Haines combined these wood attributes into a Loudness (L) index, which indicates the potential for greater loudness.

“Low density, high Young’s moduli [the stiffness of the wood], and low damping contribute to high values of L,” which the author’s noted is usually a desirable quality in an instrument. The L value effectively measures the wood’s properties at a certain resonance.

Dr Bernard Richardson of Cardiff University continues to study the properties of wood today and says this measure has some drawbacks.

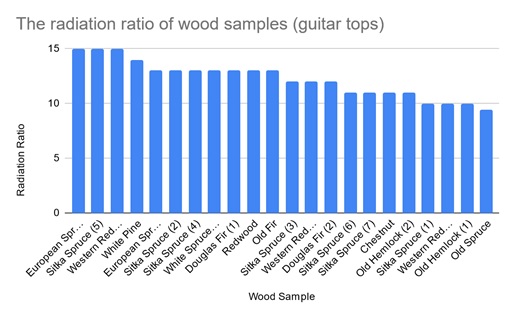

He says the Radiation Ratio – another measure of acoustical power minus the impact of damping – is a better measure of wood’s properties. This ratio (technically a measure of the stiffness to density ratio) better describes the contribution of modes in radiating sound above their resonance frequencies.

The diagram below shows the Radiation Ratio of several wood samples used to make guitar (and violin) tops tested by Haines. It shows some common wood types such as European Spruce and Western Red Cedar, ranked particularly highly, although there was a large variation between samples.

Spruce and Cedar: a strong radiation ratio

There are many different types of spruce, but Haines referred to European Spruce as the first choice of instrument makers (which he referred to as Picea excelsa – a now obsolete scientific term since replaced with Picea abies).

“This wood is typically fine-grained, light in color, and the instrument makers’ consensus choice above other spruce species,” according to Haines’ report.

The Radiation Ratio for one particular sample of European Spruce was as high as any of the 87 samples tested by Haines, but it was also matched by samples of Sitka Spruce and Western Red Cedar.

“Those who prefer cedar do so for its contribution to sound quality, for it splits and dents easily. Compared to spruce, this wood is less dense, less stiff and most significantly, less damped, especially transversely.”

The back of guitars have traditionally been made from rosewood, which differs from violins, which are made from maple.

Haines attributed this choice to the lower damping quality of rosewood compared to maple. This helps improve the sustain of the guitar, which is not such as issue with the violin.

Haines may have overstated the case. Energy transmission from strings to the body of the guitar is the limiting factor in energy loss and it’s losses in the strings themselves which are the major factor, especially at higher frequencies.

Sound quality is not just a function of wood species

The species of wood used to make an instrument is no guarantee it will sound great, or even that it will have a particular tone.

There are just too many factors at play, even within the same wood species, and in the construction of guitars themselves.

Luthier Trevor Gore has estimated that the material properties of wood from the same species can vary by a factor of two.

“Consequently, there is significant overlap of the material properties of one species with others, implying that wood species substitution is possible with little acoustical impact if the component is designed and built to acoustical tolerances rather than dimensional tolerances,” he wrote in a paper, Wood for Guitars, published in The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.

This is partially reflected in Haines tests. For example, one European Spruce sample had a Radiation Ratio of 15 while another (used to make a violin top) recorded just 10.

Haines speculated that the poorer-performing wood was due to bear claws in the sample (rippling in the wood fibre), which could increase the density of the wood (and internal damping , reflected in a lower Loudness value).

Dr Richardson is currently testing light-weight cedar and spruce, which exhibit similar characteristics.

“I suspect the differences then become quite small,” he says. “What matters are the actually physical characteristics – not the species.”

While the average piece of cedar at a cellular level has thinner walls, which leads to less density and stiffness (density being the key factor), these generic differences can easily vary.

“I have had samples of well-cut spruce with lower density than cedar – it’s just a quirk of how they’ve grown.”

Other differences found between the same species of wood include grain size, which can vary depending on the region where the wood was grown, and density. The density of the dark summer wood or late wood growth ring is far higher than the density of the light early spring wood, according to Haines.

The way wood is cut also has a significant effect on its acoustic properties. The traditional way to cut wood for instruments is quarter-cut style, which keeps the grain and fibre as straight as possible to maximize stiffness, says Dr Richardson. This maximizes the radiation ration for the selected wood (whatever species).

“It’s extremely rare to find spruce trees which grow without some spiral growth, so it’s well neigh impossible to get a full-width board which is quartered across its whole width or has fibres running parallel to the faces across the full width,” he says.

“There are always compromises in the best treated wood – and even bigger compromises in most wood which is cut to maximize commercial interests rather than acoustical criteria.”

No products found.