Inharmonicity is a part of the guitar’s unique sound, but if it becomes too pronounced, it can make a guitar sound harsh and dissonant.

String gauge, material, stiffness and damping play key roles in determining the amount of inharmonicity, which describes the slightly ‘off’ overtone frequencies that occur when a fundamental note is played.

A new scientific study published in The American Journal of Physics has now tested several Ernie Ball, D’Addario, DR Pure Blues, and Martin strings to determine exactly how those factors work and the exact degree of inharmonicity those sets produce.

Why harmonics matter

A vibrating string vibrates produces discrete frequencies called harmonics – many of these are a perfect integer multiple of the root note (or fundamental), which produces a pleasing sound. However, some harmonics are pulled sharp, and this effect becomes more pronounced with higher order harmonics.

A very inharmonic string may even sound out of tune with itself, which might give the string a harsh sound with undesirable resonances. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing and depends on the subjective nature of individual taste.

“The piano is a very good example of an instrument that is naturally out of tune (much more so than a guitar), and it has to be in order to reduce beats between fundamental notes and harmonics of lower notes that match the fundamental frequency,” says Professor Scott B. Whitfield from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, who co-authored the new study.

“Most of us have no problem with pianos being out of tune this way and have basically come to enjoy and accept this compromise in its sound. However, there are those that (very few) just do not like that pianos have to be tuned this way.”

A piano can produce inharmonicities of 1.5 per cent or more – well above the range 0.5-0.6 per cent range that most people can detect. Similarly, an inharmonic guitar string may produce resonances that sound harsh, making some notes sound out-of-tune (depending on the listener).

You can hear an excellent example of string inharmonicity by playing the “Sound 1 example” here at University of Cambridge Professor Jim Woodhouse’s (free) book on Euphonics. There is a noticeable difference between the three (synthesised) steel strings with diameters 0.3 mm, 0.6 mm and 1 mm given changes in bending stiffness.

String tests reveal the least inharmonic strings

The study tested the role of inharmonicity in pinned strings by examining various sets of steel and nylon guitar strings (monofilament and wound). Each guitar string was attached to a monochord apparatus, plucked at various locations, and the sound recorded with a microphone, a piezo device, and electric guitar pickup.

The study identified three traits that could help guitarists selecting strings:

- Thicker monofilament treble strings are more inharmonic than thinner strings.

- Wound bass strings are more inharmonic than monofilament strings.

- Wound strings with hex-shaped cores are more inharmonic than round-cores.

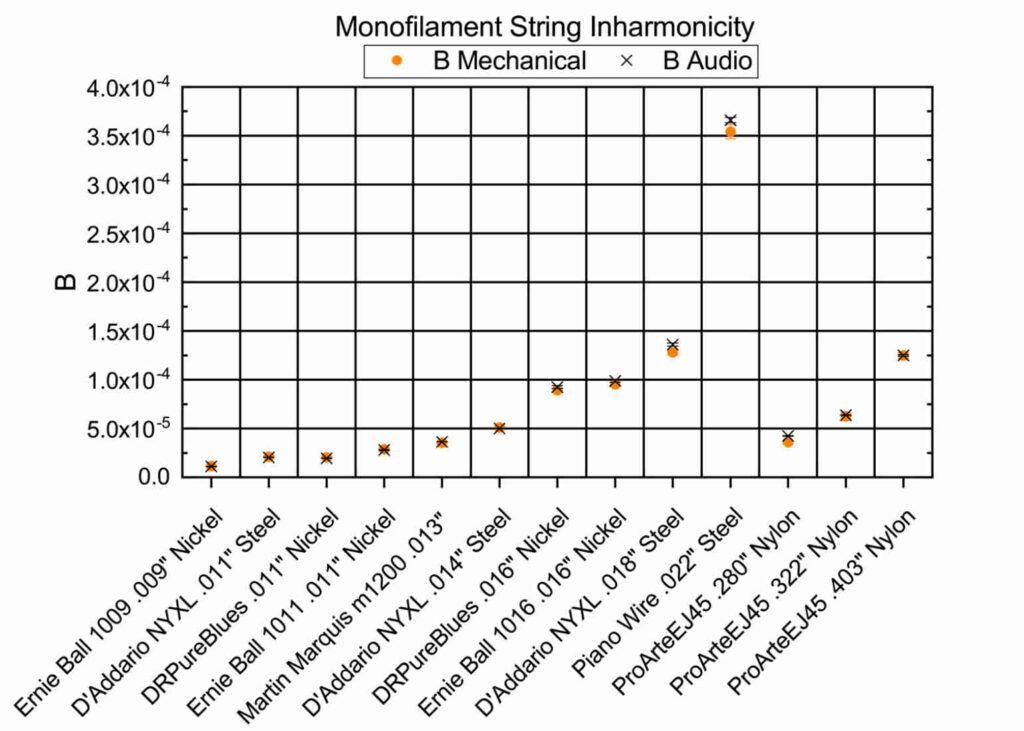

The table below shows the results of tests on monofilament treble strings: nickel, and steel electric strings, as well as nylon classical guitar strings. “One can clearly observe that inharmonicity increases for both the steel and nylon strings as the string diameter increases,” according to the study.

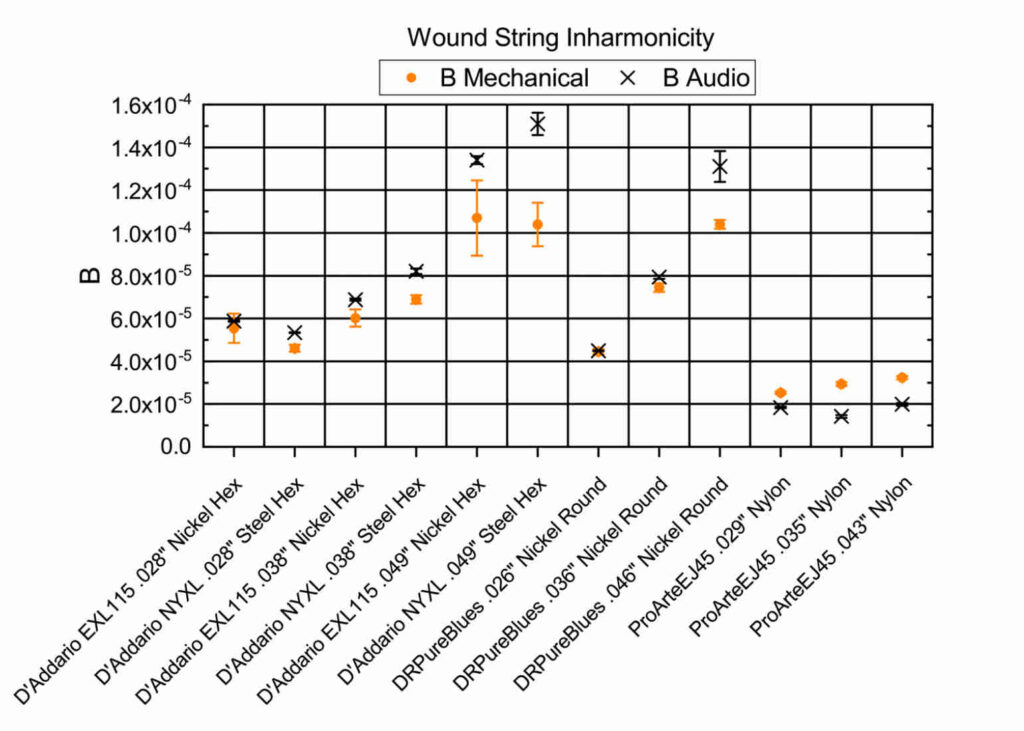

The table below shows the results of tests on wound bass strings for electric and classical guitars. It shows that hex core strings (with a hexagonal cross section core) were more inharmonic than strings with round circular cross section core.

“Modern guitar string manufacturing techni-ques favor using hex-shaped cores for the wound strings. It is possible that the sharp edges of the hex shape dig into the windings and that this interaction creates an extra restoring force that increases the inharmonicity.”

Guitarists can use this information to potentially build the most harmonic string sets by combining preferred single strings or buying full sets. The table below outlines some of the most popular sets that contain the strings.