The flamenco guitar sounds radically different than the classical guitar yet the differences in construction are subtle.

They are not separate instruments in the way that a violin differs from a viola, which are closely related but significantly different in size, pitch, and sound quality. Some have compared the difference to a violin and a fiddle, given a fiddle is a (sometimes modified) violin used to play folk music.

However, the flamenco guitar is not a derivative of the classical guitar and in fact, history suggests that Spanish guitar maker Antonio Torres (1817-1892) – who standardised the size and form of the modern guitar – made no such distinction. American luthier Ervin Somogyi suggests the distinction came about more recently:

Even though these instruments are played in distinctly different musical networks, there is evidence that there was no meaningful distinction made between “classical” and “flamenco” guitars, by either the makers or even most musicians, until the 1950s.

Ervin Somogyi, The State of Contemporary Guitar

While the violin-fiddle analogy is far from perfect, it does hint at a cultural divide. Paco de Lucía once described the relationship between the two camps in this way:

It was very clear to me that the first people we had to please with our work was ourselves. In our recordings, there was certainly a great deal of rage. I have always had it, as did Camarón. I do not know what motivated his [rage] but I know that mine has been with me since childhood in the world of flamenco, and even more outside of it… especially in the world of the classical guitar where flamenco guitarists were treated with absolute contempt. I have always played with that complex and with the rage to affirm that what I was doing was valid. That is what motivated me to play with the speed with which I play. And that velocity, it can’t be studied because it is a way to fight against insecurity and fear.

Paco de Lucía. La Cana, number 6, pages 4-6, publisher Espana Abierta, 1993.

Let us now delve into the technical and cultural differences between the two instruments and how they came about.

A lower action

A flamenco guitar with a low action and higher tension strings can help produce the characteristic flamenco attack. The wound E string might be extremely low at just 1.6 mm (1/16″) at the twelfth fret compared to a classical guitar at around 3.2 mm (1/8″).

The action of the wound E string measured at the 12th fret may be as low as 1.6 mm (1/16″) on a flamenco guitar. A classical guitar’s action may be double that, at 3.2 mm (1/8″). Such a low action can have consequences for the type of flamenco guitar strings that are best suited to the instrument.

Why such a low action? It makes the guitar easier to play for extended periods when accompanying dancers. It can also be easier to perform difficult left-hand techniques such as extended slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs). A low action tends to produce a characteristic flamenco buzz when the low-set strings hit the frets, although this is a matter of taste. There are also downsides: a low action can reduce the volume of the guitar because the strings have less room to vibrate and deliver energy through the soundboard.

These are clear trade-offs each guitarist must assess – the decision ultimately comes down to personal preference. Shaving down or replacing the nut or bridge can lower the action, although different guitars have their own natural limit.

There is some evidence that early guitars were built with a lower action that since become associated with the flamenco guitar, according to luthier Richard Bruné. He examined a 1904 Jose Ramirez I (1858-1923) classical guitar with an action of less than 1.6 mm (1/16″) at the twelfth fret, suggesting that classical guitarists began to prefer a higher action post-WWII.

No products found.

Golpeadores or tap plates

A characteristic technique of flamenco guitar is the golpe – the percussive right-hand finger tapping with either flesh or nail on the soundboard. This would damage the soundboard without protection, which is why flamenco guitars have a golpeadore glued to the face of the instrument.

Older guitars often had clearly visible, plastic golpeadores. Today, they are made of thinner, transparent plastic.

Peghead tuners

Rosewood or ebony peghead tuners were standard until Antonio Torres invented geared machine head tuners. It was some time before geared machine head tuners became dominant because they were initially far more expensive than peghead tuners. The choice of tuner has no bearing on the sound of the guitar. Few guitars, like the one below, are now built with traditional peghead tuners.

Wood: blanca versus negra

Traditional flamenco guitars tend to be made from light woods such as cypress. Classical guitars tend to be made from dark woods such as rosewood. The different woods naturally have different acoustic properties: cypress produces a sharper sound while rosewood produces more sustain and color.

However, there are many elements that affect a guitar’s sound. Many classical and flamenco guitarists throughout history have played both types of guitar depending on what they wanted to achieve.

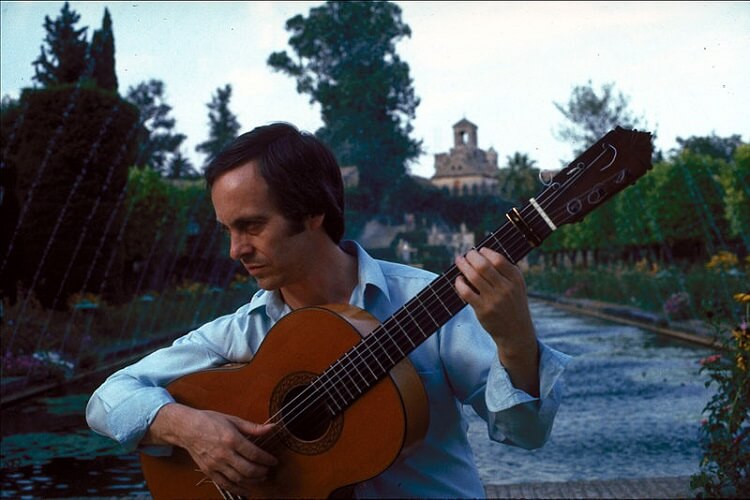

Some scholars trace the distinction between the flamenco and classical guitar to Andrés Segovia (1893-1987), who elevated the classical with one hand while pushing flamenco away with the other.

Segovia’s early training was in flamenco and he played a blond 1912 Manuel Ramirez/Santos Hernandez guitar until 1937. But after offending Santos Hernandez, who was the leading Spanish luthier of the time, he was forced to look abroad for another guitar. He turned to German luthier Hermann Hauser who made him a rosewood guitar modeled on a Torres guitar. (You can see a comprehensive list of guitars made by Hermann Hauser, and which guitarists play them today, here.)

As Segovia’s popularity soared, his choice of a rosewood instrument became firmly associated with the classical guitar.

No products found.

Weight and depth

Flamenco guitars are said to be lighter in weight than classical guitars.

However, there is some historical evidence that classical and flamenco guitars were both much lighter.

The wood found in Torres’ guitars (whether light or dark) was just 1.0 to 1.2 mm thick – half that of modern guitars at around 1.5 to 3.0 mm. Heavier applications of modern varnish using industrialized techniques rather than time-consuming, hand-applied French polish also add extra weight, according to Bruné.

The body of a flamenco guitar is also said to have less depth when viewed from the side (a shallower body can also decrease the maximum volume of the instrument).

The combination of these factors (action, golpeadores, peghead tuners, wood, weight and depth) mark real differences between classical and flamenco guitars but history suggests they are founded more in culture than practice.